Opportunity knocks for everyone. In some cases, opportunity knocks, rings the doorbell, shouts into your Ring camera, tosses pebbles at your bedroom window, then goes out to its convertible in the driveway and starts singing “Thunder Road.”

Kevin Gausman and Yoshinobu Yamamoto were both terrific, but all duels end with one man standing and the other getting stabbed. Yamamoto twirled his second straight complete game, giving him the first streak of playoff complete games in 24 years. Gausman fell off the tightrope in the seventh inning, as home runs by Will Smith and Max Muncy put the visiting team in front for good. The Dodgers’ 5-1 win wasn’t as splashy as Toronto’s home run party the night before, but it evens the series.

Gausman was all but out of the first inning. He had two strikes on Freddie Freeman, who’d fouled off a splitter at his ankles, then a middle-middle fastball, then another heater up at his hands. Gausman went back to the splitter, the pitch that made him famous, and buried another.

Just not deep enough. Freeman reached down and drove it to right field for a double. Two pitches later, Smith followed a slider out past the outside edge of the plate and looped it to center to plate Freeman.

In the bottom of the inning, George Springer took a fat fastball from Yamamoto and drove it into the left field corner for a double. The very next pitch jammed Nathan Lukes, but his Texas Leaguer dropped between the Dodgers’ defensive shells to put runners on the corners for the meat of the Blue Jays order.

Vladimir Guerrero Jr. has spent the past month answering when opportunity knocks. In what everyone north of the Rio Grande could see was a massive moment, Guerrero poked and parried one splitter after another, but sputtered when Yamamoto reached into his Mary Poppins bag of pitches and pulled out a 2-2 curveball. Alejandro Kirk and Daulton Varsho went quickly thereafter, and all of a sudden the Blue Jays had squandered their chance to put their boot right back where it had been 20 hours earlier.

Yamamoto and the Dodgers kept giving Toronto chances. Ernie Clement continued his streak as the luckiest hitter on the planet when Freeman inexplicably overran an infield pop-up:

Ernie Clement is gifted a single here on a missed catch by Freeman.

He is now up to a 58% swing rate on the first pitch this Postseason.

The league average swing rate on the first pitch was 32% in the reg. season.#WorldSeries pic.twitter.com/DyHQEl88mb

— Inside Edge (@IE_MLB) October 26, 2025

Runner on first, nobody out, xBA .000. Nothing came of it.

Finally, in the third, the Blue Jays got on the board. Springer wore a Yamamoto fastball off his forearm, advanced to third on Guerrero’s one-out single, and scored on Kirk’s sacrifice fly. But Toronto only scored one this time, and Yamamoto found his footing, setting down the Blue Jays in order in the next four innings.

That one run kept the Jays in it, because after Smith’s first-inning single, Gausman retired the next 17 batters. This was classic Gausman, almost all fastball/splitter. It’s going arm-side, but with God knows what vertical break and at God knows what velocity. Hit it, if you can.

Most of the Dodgers couldn’t. Teoscar Hernández faced Gausman three times and struck out each time up, tied up and cooked like a roulade. Gausman had been pulled in the middle of the sixth inning in five of his six career postseason starts; this time, he not only skated through six, he got the first out of the seventh on his first pitch of the inning, and only his 66th of the night. With John Smoltz in the booth, Gausman was pacing himself for a Jack Morris-like 10-inning complete game.

But while Gausman was gobbling up outs, he was doing so in a manner that prefigured what was to come.

Gausman’s splitter is tremendous. It’s godlike. It’s unsporting. In order to throw it effectively, he needs to throw his four-seamer as well; the fastball is the jab, the splitter is the power punch. This regular season, opponents hit .230 and slugged .380 against Gausman’s fastball, which is actually quite good for a four-seamer. Last season, they hit .281 and slugged .475, which is less so.

If you’re going to get Gausman, you’re going to get the fastball.

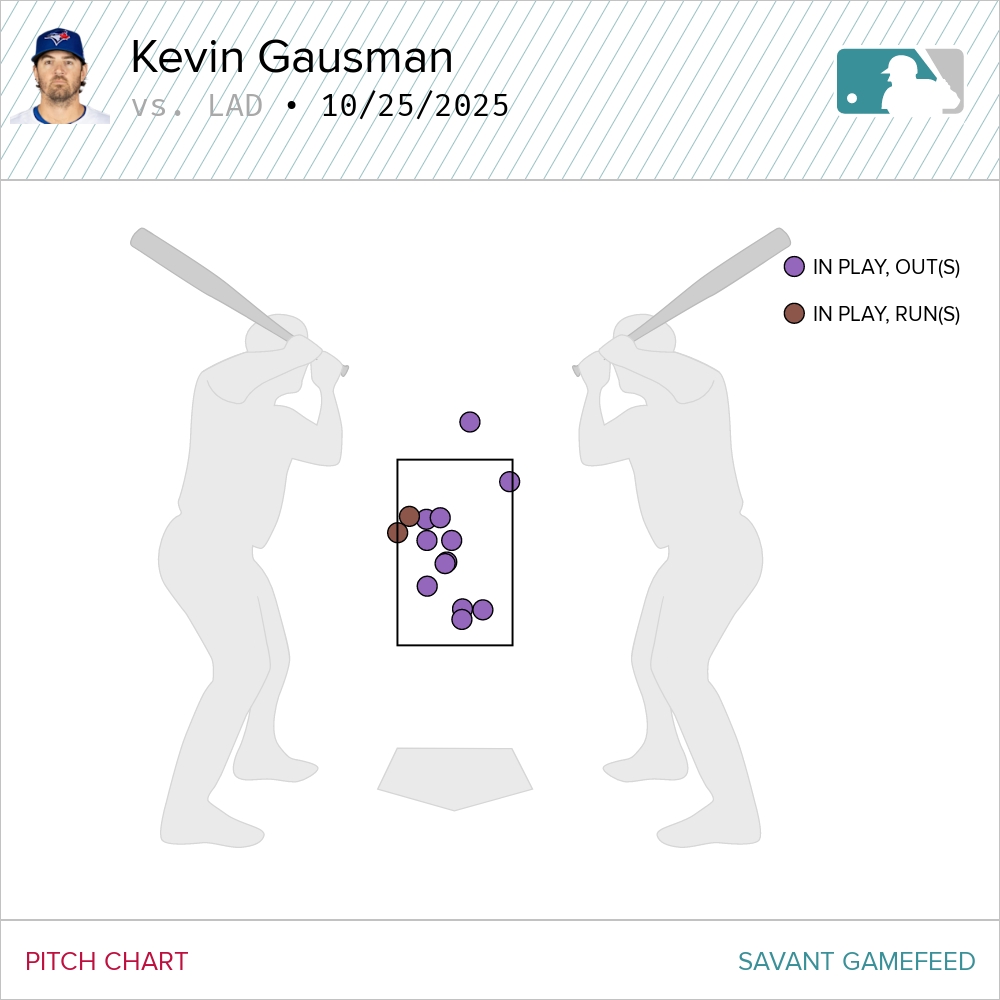

For six innings, the Dodgers weren’t getting the fastball at all. And it’s not because it wasn’t hittable. The Dodgers swung at 25 of Gausman’s 49 fastballs, whiffed only three times, and put 14 of them in play. Here’s where those were located:

More than half of Gausman’s batted fastballs registered as “Hard Hit” by Baseball Savant’s definition. But of the first 12 fastballs the Dodgers put in play, only one traveled more than 308 feet. Last night, Varsho hit a rare left-on-left homer off Blake Snell, enabled by one of the worst pitches you’ll ever see Snell throw, a middle-middle pipe shot that any batter with average power ought to hit 400 feet without breathing heavy.

In the fourth, Gausman threw a pitch to Freeman that was, if anything, even easier to hit. First pitch, higher in the zone, only 93.6 mph. Freeman got most of it, driving it Varsho’s way at 108.4 mph, but didn’t get all of it. Two pitches later, Smith took just as meaty a fastball and got under it. Gausman concluded the sixth by tying up Shohei Ohtani and Mookie Betts for consecutive pop-outs.

As good as Gausman was, he was getting away with it a little. In the seventh, his luck ran out. This was arguably a better pitch than the ones the Dodgers had been knocking into the ceiling all night, veering hard right and into Smith’s hands. But he tucked his arms in, and out the ball went:

Two batters later, Muncy followed with an opposite-field shot on a nearly identical pitch. That did it for Gausman, and the Dodgers tacked on two insurance runs off the ubiquitous Louis Varland.

The Blue Jays never fought back. Because sometimes, when opportunity knocks, Yoshinobu Yamamoto sneaks up behind it, covers its face with a rag soaked in chloroform, and hides its unconscious metaphorical body behind a metaphorical topiary.

Sorry, I’m getting carried away.

By the time the game ended, it was hard to remember that for the first three innings, Yamamoto looked genuinely shaky. He was leaving fastballs in bad places, running deep counts, working through traffic. Had the Blue Jays converted three straight lead runners on base into more than one run, they might once again have gotten to see the face Emmet Sheehan makes when he’s trying to make himself invisible amid a nine-run inning.

But after Guerrero singled to put Springer in position to score the Jays’ only run, Yamamoto didn’t allow a single baserunner for the rest of the night.

Yamamoto ended the evening on a string of 20 consecutive Toronto hitters retired. Coupled with Gausman’s 17-batter streak earlier in the game, this was the first time in major league playoff history that both starters in a postseason game retired 14 or more batters in a row.

You’d think that these two right-handed pitchers, both masters of the splitter, would have similar styles. Not so. While Gausman rode two pitches almost exclusively, Yamamoto sprinkled in all six of his in different proportions each time through the order:

Yoshinobu Yamamoto’s Pitch Usage by Time Through the Order

| TTTO | Fastball | Sinker | Cutter | Splitter | Curveball | Slider |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 8 | 0 |

| 2 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| 3 | 6 | 0 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| 4 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

| CSW | 7 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 9 | 2 |

| Hits | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Source: Baseball Savant

Having overexposed his splitter early, he pulled back in the mid-game, leaning on his cutter, then his breaking stuff, before going back to his moneymaker late, like Lynyrd Skynyrd closing with “Freebird.”

As the innings turned over and Yamamoto’s pitch count stayed in a reasonable range, Dodgers manager Dave Roberts never encountered a reason to take his starter out.

When Justin Verlander struck out 13 Yankees over nine innings in Game 2 of the 2017 ALCS, it had been exactly a year since the last postseason complete game. It was eight years to the day before the next — Yamamoto, in Game 2 of the NLCS against Milwaukee. Yamamoto repeated the trick in his very next start, 11 days later. In so doing, he became the first pitcher since Curt Schilling in 2001, and the first Dodger since Orel Hershiser in 1988, to pitch a complete game in consecutive postseason starts.

Like Gausman, Yamamoto wasn’t on some 30-whiff strikeout binge. He got 15 whiffs and eight strikeouts, which is good, but not spectacular. But he didn’t walk anyone. He threw 73 strikes out of 105 pitches. When he gave up hard contact, he kept it on the ground.

The exemplary late-game Yamamoto at-bat, to me, was the one that ended the seventh. Toronto manager John Schneider reached for his last card to play, Bo Bichette, who’d gone 1-for-2 with a walk on one knee in Game 1.

Bichette laced the ball into the hole — 107.7 mph, the third-hardest batted ball of the night for either team — but within the range of Betts. The Dodger shortstop, obviously cognizant of the fact that Bichette could not outrun the tide in his current condition, took plenty of time to line up an accurate throw. Betts, and Yamamoto, did exactly what was required to win. No more, no less.

The air of invincibility is gone after getting boat raced in Game 1, but the Dodgers will no doubt come home satisfied with a split in Toronto. After tasting canvas for the first time since (I’d argue) last year’s NLCS, they did to the Blue Jays what they’d done to the Brewers and Phillies in the past two rounds: Waited out their opponent’s ace and nosed over the line late. When opportunity knocked, the Dodgers answered.